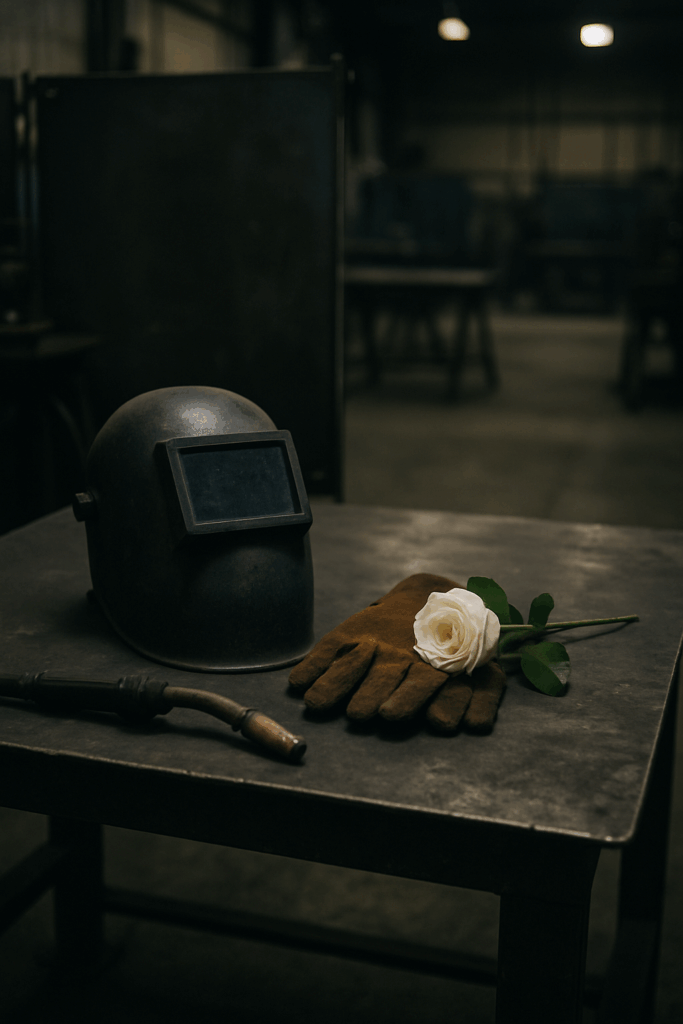

Amber Czech was 20 years old, a welder in Minnesota who loved her job and was proud of the trade she chose.

She went to work, stepped into her routine, and never made it home.

According to reports, a 40-year-old male coworker first walked away from his own workstation. Then, he picked up a sledgehammer at Amber’s station and struck her multiple times. Afterward, he admitted to police that he “didn’t like” her and had been planning to kill her “for some time.” Amber died at the scene from blunt force trauma and blood loss.

CBS News+2WKRC+2

Her family describes her as outgoing, hardworking, and an excellent welder. Early on, she discovered her passion for the craft in high school and later completed a welding technology program at Alexandria Technical & Community College. New York Post+1

This isn’t just a crime story. It’s an indictment of the conditions we ask people—especially young women in the trades—to work under.

What Amber’s murder exposes about our industry

This situation hits several pressure points we can’t ignore:

- Workplace violence is a safety issue, not an HR problem.”

Many safety programs obsess over falls, lockout/tagout, confined spaces, rigging plans… and say almost nothing about the risk of violence from coworkers. Amber’s death is a brutal reminder: the person who kills a worker might not be a stranger on the street. It might be someone on the crew. - Leaders still minimize warning signs and conflicts.

The alleged killer told investigators he’d been planning to kill her “for some time” and admitted he didn’t like her. CBS News+1

We don’t know every internal detail, but we do know this. In too many shops and jobsite cultures, leaders tolerate people who are openly hostile, disruptive, or unstable, as long as they can produce. - Women in construction face layered risks.

We celebrate “Women in the Trades” in our marketing, but on the floor and in the field, many women navigate:- Being outnumbered.

- Being harassed or undermined.

- Being told to “toughen up” instead of being taken seriously when they feel unsafe.

When a young woman is murdered by a coworker who “didn’t like her,” it forces the question:

What did we build around her to protect her? Or did we just drop her into a culture and hope for the best?

- Production still outruns people.

Advanced Process Technologies paused production for the week and expressed heartbreak and support. WKRC+1

That’s the minimum. But industry-wide, we have a pattern: tragedy → statement → brief stand-down → back to business as usual. Culture doesn’t shift on condolences—it shifts on confrontation and accountability.

The weariness: “How many times are we going to see this?”

If you’ve been in this industry a while, this doesn’t just land as “shocking news.” It lands on top of:

- Stories of workers killed by equipment, vehicles, falls—and now coworkers.

- Quiet conversations between women on the job: who to avoid, where not to be alone, which shift feels less safe.

- Years of seeing serious behavior brushed off as “he’s just like that,” “she’s overreacting,” or “it’s not that bad.”

There’s a deep tiredness that comes from:

- Knowing our people go to work with unspoken fear—not just of accidents, but of the human beings around them.

- Watching leaders talk about “family culture” while tolerating bullying, intimidation, and simmering resentment.

- Feeling like every preventable death becomes a 48-hour talking point and then disappears.

That weariness is dangerous. It makes people numb, and numb people stop pushing.

The anger: “This was not inevitable.”

Anger is not only understandable here—it’s necessary.

- Amber did exactly what we encourage young people to do:

She found a passion in high school, trained, entered a skilled trade, and showed up ready to work. She trusted us—the adults, the companies, the system—to make that leap worth it. - She wasn’t in a dark alley at 2 a.m. She was in her workplace, on the clock, doing her job in a controlled environment.

- A coworker openly admits he didn’t like her and had been planning to kill her “for some time.” That is not a momentary outburst. That is premeditated, festering hate inside a workplace that somehow didn’t catch it, didn’t act on it, or didn’t have the mechanisms to surface it safely.

Oxygen+1

If that doesn’t make company leaders angry—if it doesn’t make us all angry—then our empathy is running on fumes.

What companies must do now: Take a position and enforce it

If you lead a construction company, a fabrication shop, a plant, or a project, neutrality is not an option. “We are heartbroken” is not a strategy.

Here’s what taking an absolute position looks like:

1. Declare that people’s safety includes protection from each other

- Put it in writing and say it often:

“No one will be allowed to threaten, terrorize, or harm coworkers here—verbally, emotionally, or physically. If you do, you will not work here.” - Elevate workplace violence prevention to the same priority as fall protection and lockout/tagout.

2. Build a real workplace violence prevention plan

- Conduct risk assessments that include interpersonal threats, not just physical hazards.

- Train supervisors and leads to recognize:

- Escalating hostility

- Obsession with a coworker

- Threatening comments, stalking behavior, or “jokes” about harm

- Establish clear protocols for:

- Reporting concerns confidentially

- Removing individuals from the workplace while you investigate

- Involving law enforcement and mental health professionals when needed

If your “plan” is just a paragraph in the employee handbook, you don’t have a plan.

3. Protect and amplify the voices of women and underrepresented workers

- Make it safe to say: “I don’t feel safe working with this person.”

When someone raises a concern—especially someone from a group that is often dismissed—treat it as actionable data, not drama. - Ensure that women and younger workers are included in safety committees and risk reviews, covering both behavioral risks and task-related hazards.

4. Hold leaders accountable for the culture—not just the numbers

This is where the accountability you mentioned becomes real:

- Tie foremen, superintendents, shop managers, and executives’ evaluations and bonuses to:

- Psychological safety scores

- Validated and resolved reports of harassment or threatening behavior

- Turnover patterns among women and other underrepresented groups

- If patterns of bullying, harassment, or unsafe behavior linger on a crew, ask:

- What did the leader know?

- What did they do?

- Why wasn’t it escalated sooner?

And if the answers aren’t good, change the leadership. Period.

5. Engage all your people in this—not just HR

- Talk about Amber’s story and others like it in safety meetings and leadership huddles—not as morbid gossip, but as a case study in what cannot be allowed to happen again

- Ask your teams:

- “Where are you seeing unchecked hostility or intimidation?”

- “Who feels unsafe but hasn’t said it out loud yet?”

- Make it clear that protecting each other is part of the work, not an extra.

The bottom line

Amber Czech was a young welder who did everything we tell our kids and students to do:

Find your passion. Learn a trade. Show up and work hard.

She should have had 40 years of welding, mentoring, and living ahead of her. Instead, her life ended on a concrete floor because a coworker who “didn’t like her” had both opportunity and intent—and nothing stopped him.

If we respond only with sadness and sympathy, we are silently accepting the possibility that this could happen again.

Companies must:

- Name workplace violence as a core safety risk.

- Build serious systems to prevent it.

- Hold leaders and teams accountable when warning signs are ignored.

We owe that—not just to Amber’s memory—but to every young person we’re asking to trust us with their lives when they step onto our jobsites and into our shops.